![]()

Welcome to my Yamaha DX7 page! After checking my site statistics, it became apparent that search engines and other music sites were directing significant numbers of people directly to this page. This is cool, but please be aware that this is only one of many pages on my site, and if you use the link at the bottom of this page to return to my home page (or click here), there you will find additional resources of interest. For example, a mailing list for keeping up to date with the latest, and a noticeboard for posting questions/messages for all to see.

Ever since the inception of this, my home page, I have been both surprised and impressed with the level of interest shown for the Yamaha DX7. And here I was thinking at the time that there would likely be few remaining DX7's still intact, let alone dedicated musicians playing them. But I was to be pleasantly surprised. Indeed, I receive perhaps three times the number of E-mails from DX7 players than players of the much later Korg instruments I also support - more extensively!

University study along with employment and domestic commitments have conspired to allow me less time with music as of late, and even less time for my home page. I regret not being able to respond quickly to all emailed queries as a result. Queries have been largely varied, although I have noted a disproportionate number of people still asking for help in transferring the 666 banks of patches offered on this page, to their DX7. Although I have explained this process by posting a response on my noticeboard, it was some time ago. I will elaborate again here, for those still having trouble with this task...

To save on download time, the patches have been compressed in ZIP format, and I assume all visitors to this home page have at least a basic knowledge on downloading and uncompressing such files. Once 'unzipped', one is left with a large number of files with an SYX extension. Each of these files represents a bank of 32 patches (Yamaha call them algorithm's). So how does one 'get' each of these banks into his/her DX7 to play them, hear them, enjoy them? The answer is from the hard-drive, via the sound card (often, or some other card with a MIDI OUT port), MIDI cable, your synthesizers MIDI IN port, and ultimately into the DX7's memory chip(s). Aside from the above mentioned hardware, you will also be needing a software application to set the data in motion. More than one such program exists. To date I have been using MIDILIB for this, and MIDILIB can be downloaded for free from my SOFTWARE page. MIDILIB is a Yamaha DX7 librarian (a library of sounds, rather than books), that includes the function of transmitting system exclusive data to an external device. One further point is that you must remember to switch 'memory protect' on your synthesizer to 'OFF', so it will accept the system exclusive stream of data. If you are still having problems in achieving goal, please either post a query on my noticeboard, or drop me an email. Please be specific and concise in any query, so as to ensure a helpful response. Good luck!

Your host,

Chris.

![]()

|

"The DX7 was immediately and universally praised and immediately and universally sought after. From 1983 to 1985, no other synth could get a look in. And this was not simply an important product in synth history; it was the key pivotal instrument. The DX7 not only redefined what a synthesizer sounded like or could do but also redefined the synthesizer market."

"The DX7 did not happen overnight. This was not some idea scratched out on the back of a cigarette packet and knocked out within the year. The first DX7's may have steamed out of Osaka in 1983, but the story actually began in California 15 earlier...."

"...Stanford University electronic music composition teacher John Chowning [was] experimenting with vibratos in the late 1960's until he discovered that he could produce musically complex, harmonically interesting results by modulating one sine wave with the output from another, using high speed vibratos. Thus in 1967, the seeds of modern Frequency Modulation (FM) synthesis were sewn. (FM as a concept had already been broadly accepted, but Chowning's work made it controllable and valid in the musical mainstream.)

"Chowning did not run from his studio on campus screaming 'Eureka!' Instead, he tinkered away for a number of years, perfecting this, recalculating that, making noises and drawing the occasional scathing comment from colleagues who figured that he must be using up all the University's quota of oscillators, such was the succession of harmonically rich sounds that continued to emanate from his wooden hut of a studio on campus. Of course, he was not. He was using just two; one as a carrier, one as a modulator.

"In 1971, digital synthesis guru Max Matthews of Bell Labs told Chowning that if he could tame his system to make recognizable brass and organ sounds, he might have a salable product on his hands. He approached the Stanford's Office of Technology Licensing with his discoveries, and they approached a number of American organ manufacturers to see if they were interested in acquiring this new technology.. They were not. Wurlitzer, Lowry, Hammond and others all turned the offer down..."

"More as a last-ditch effort than anything else, Stanford turned to Yamaha, who produced a small range of Electone organs (at this time, everyone figured FM would only be of interest to organ manufacturers) and had an office in California.

"A young engineer by the name of Mr. Ichimura was dispatched to Stanford to check things out. Mr. Ichimura understood digital and, as an engineer, appreciated the concept of FM in radio terms. So, it only took him about ten or fifteen minutes to comprehend the essence of what Chowning had cooking. Chowning knew that Ichimura was impressed by what he'd seen and heard and so was not surprised when he learned that Yamaha wanted to take out a year's exclusive option on FM.

"In the ensuing few years, a number of things developed. Under the wing of Yamaha's organ division (the division that had actually taken out the option), a prototype FM instrument was built under the direction of Dr. Mochida, entitled the 'MAD.' This monophonic FM synth, built in 1973 by two young engineers by the names of Hirokato and Endos, is possibly the first all-digital synth ever made. By 1975, a polyphonic version had also been built.

Over at Stanford, meanwhile, things weren't quite so rosy. John Chowning's job was as an electronic music composer and teacher at Stanford, and the University's approach was very much this: 'To hell with all this fancy synthesis stuff, where are the compositions?' To put it as bluntly as Californians get, they 'let him go.'

"When Yamaha returned to Stanford in order to 'do the big deal' - take out a ten-year license on FM - Chowning was nowhere to be seen (actually, he was in Europe). All very embarrassing. Somewhat hastily, the University contacted Chowning and offered him the post of Research Associate, a job he says he was by then in no position to turn down. Installed as Director of the University's Center for Computer Research and Musical Acoustics (CCRMA, known as 'carma'), Chowning was later offered a professorship in 1979.

"As an aside, one of the many stories that grew up around FM is that Dr. Chowning received no monetary reward for his invention. Not true. As a member of the faculty in 1970, it was not compulsory to turn over licensing of any technology developed while at the University (as it is now), but it was the most obvious and perhaps the wisest move. Chowning signed the copyright of FM over to the University in return for a royalty, and in turn, the University assigned a license to Yamaha. Dr. Chowning may not presently be living in a Bel Air mansion, but he appears happy with what he made out of the deal. 'People say to me, 'You'd be a billionaire if you'd kept it to yourself,' he says. 'And I say, right. Or I'd have got nothing.' As it is, all parties appear to have been scrupulously diligent about royalty payments, and no whiff of dissent hangs in the air. While Chowning's deal with Stanford is privileged information, the university itself is said to have reaped more than $20 million in license fees and outright payments, which it used, to its credit, to move CCRMA from its 'shed' on campus to a splendid, brand-new, specially designed building.

"But back to our story. With Chowning ensconced at Stanford again and a new ten-year license in place, serious work began on producing marketable products utilizing FM synthesis. There was, however, one final shootout between two technologies that Yamaha had been developing side by side: FM and a home-grown 'summation' additive synthesis. Chowning, who by now was paying occasional visits to Japan, recalls a big meeting at which the two competing technologies were displayed and discussed. In the end, FM, which wasn't dependent upon digital filters that would have been very expensive to produce, won out. Not only was it more memory-efficient, but it also had the potential for far greater player-control.

"From then until the DX7's launch in 1983, John Chowning only occasionally heard whispers of "DX" as he slipped through factory corridors on his visits to Japan. The GS1 was the first FM-sporting instrument to be released, in 1981, though in spite of the ripple of excitement it caused in the industry, the GS series was always intended to be a market-tester."

With the launch of the DX7, all hell was let loose; Yamaha simply couldn't make enough of them. But by now, this was far removed from John Chowning`s world. In fact, he saw and heard his first DX7 synthesizer in a bar in Palo Alto. Chowning remembers the occasion vividly: 'My wife and I had been out to see a movie and we stopped off at a local bar for a nightcap I knew the keyboard player in the bar, and when he saw me he waved me over excitedly to come and see this incredible new instrument he had sitting on top of his piano. I was astonished. It was an awesome moment. I had no idea that people had been waiting in line to buy DX7's. I had no idea at all.'"

"And so the product of Chowning's (and many other's) labors ended up as a 16-voice polyphonic digital synthesizer, offering 32 internal memories plus a ROM/RAM cartridge slot. The DX7 keyboard is not weighted, but it responds to velocity and aftertouch. Further expression can be extracted from a Breath Controller, Yamaha's own invention, a mouthpiece/pacifier affair by which you can more or less convincingly simulate the breath-to-tone response of a wind instrument. (Unfortunately, very few players felt comfortable with this object stuffed into their mouths)

"The DX7 panel is not an object of particular beauty. There are plenty of dedicated controls, though switches are squishy "membrane" types and the display screen is minuscule. Along the top of the panel runs a collection of "algorithm" diagrams, so you can see at a glance the type of sound you are likely to produce (effectively) using each of these oscillator configurations. An envelope generator and a keyboard-level scaling graphic are perched on the end.

"Chowning's FM theories manifest them on the DX7 as a series of "operators" (which can be thought of as oscillators) that the instrument offers to the user in a number of different configurations or "algorithms." The operators are all sine waves, and each can be either a carrier wave or a modulator wave, depending on its position or relationship with another wave in a particular algorithm. The DX7 can use six operators per voice.

"DX7 programming is commonly, though not a little unfairly, perceived as impenetrable. Perhaps it was unwise of Yamaha to splash about words like 'operator' and 'algorithm' when 'oscillator' or 'voice' or 'shape' might have been less intimidating.

"In any given program, the novice programmer can simply switch operators on or off and begin to learn what role each performs within a sound, but things do get rather more involved when you consider that each operator can also specify a particular pitch, volume, envelope and such, and so each is almost a complete mini-synth in its own right. In a flat operator-plus-operator algorithm, the system can work as simply as drawbars on an organ, but once operators begin to interact, then the sonic results become vastly more complex and unpredictable (which is why the system sounds so good, of course). In fact, a maneuver such as changing an envelope setting of the top member in a stack of interacting operators can exert all manner of unexpected influences on those further down; it is this level of programming intensity that has led to the theory that the three essential ingredients of FM programming are trial, error and luck.

"The individual parameters do not befuddle as much at the general level of interaction. Indeed, Yamaha retained many analog-style features and terminologies. The LFO, for instance, offers triangle, saw up/down, square, sine and random waves and can be set in terms of speed, delay, routing (pitch or volume) and amount. Although the envelope generators, which Yamaha bravely but wisely entombed in silicon rather than taking the 'flexible' software route, have their rate and level system emblazoned on the control panel, such multistage envelopes are notoriously complex to set, especially without any help via movable graphics on the display screen. If I may borrow from Howard Massey's excellent book The Complete DX7, one rule of thumb is to remember that envelope generator control over a carrier will affect volume over time and envelope generator control over a modulator will similarly affect tone. There is also a separate four-stage pitch envelope generator. (The tangible benefit of hardware envelopes, by the way, is speed.)

"Many parameters that are sewn into the fabric of a program on more modern instruments are global parameters on the DX7. These include pitch bend range, mod wheel assignments, aftertouch response, glissando, poly/mono assign, etc. All of these are called Function parameters and are accessed using the same buttons as the presets or voice programming parameters. Said buttons - the offending squishy membranes - thus have three separate purposes."

"Though FM programming has been somewhat unfairly classified as hopelessly complex, it is reasonable to say that 155,000 out of the instrument's 160,000 customers have been content to play the presets. Credit for this fact goes squarely to the two consultant programmers who voiced the DX7, Dave Bristow in the UK and Gary Leuenberger in the U.S. This Lennon-and-McCartney team of programmers, whose work spans from the GS1 to the SY series, extracted every possible ounce of musicianship from the DX7, ranging from the classic Fender Rhodes electric piano facsimile (which has since entered synth folklore, known as "DX piano' to all subsequent copyists), to the sonorous collection of fretted and fretless basses, to hand percussion, bells, marimbas, ripping brass and sound effects.

"Leuenberger explains how he created the DX piano: 'It was a very intuitive thing that began on the GS series, which has just four pairs of operators. Having come from a background of B-3s, I knew what to expect by adding sine waves together. After learning what happens by changing the envelope for a modulator and a carrier, I made the foundation 'rubbery' tone with one-to-one ratio but with different envelopes. Then I did the same using another pair of operators and detuned one against the other. With a third pair, I produced a sound like something hitting metal, which, to my intuitive sense, sounded like a 'tine' [Rhodes metal rod] sound, so I added that in. Finally, by apportioning velocity control to these components, it turned into this beautiful, real-sounding musical instrument.'

"Bristow and Leuenberger also recommend embracing the concept of "stuff." Stuff is some character-inducing component part of a sound that can be used in several tones. Bristow explains creating a Wurlirzer tone: "I had this real high operator noise ("stuff") which I added to 2:1 ratio square-wave, clarinet type of sound, so providing the fart necessary for a convincing Wurlitzer electric piano. Put a bunch of velocity on it and some tremolo... that's how it was made.

"Adding non-integer, weird ratios for just a fraction of a second colors your perception of a sound. Later I discovered that this wasn't actually FM at all, but AM, amplitude modulation - that the frequency is going up and down so much over a short period of time that they were creating their own side bands."

"Bristow and Leuenberger's experiences with DX7 programming were moving (Bristow remembers the final sound presentation meeting in Japan at which all the engineers were packed into a room with tears in their eyes, some of them hearing music on this instrument for the first time after laboring over oscilloscopes and technical data for two years), madcap and occasionally murderous (they had just one week to compile the instrument's first 128 presets), but both agreed, when interviewed recently, that they would do it all again for the same unmentionably low fee...."

"...there can hardly have been a player in the 1980s who did not use the DX7 or one of its multifarious spinoffs. There also grew up a whole industry of DX7 add-ons and support products, such as Grey Matter's E! expansion kit, which bolsters the patch tally to 320 - each one complete with its own dedicated function parameters - while improving the MIDI spec to include local on/off, full 16-channel access and wide-ranging MIDI filtering and also adding some simple tone controls and the possibility of patch layering.

A similarly user-installable mod from Group Center called DX Super Max beefs up the program count to 256, offers patch layering and function programming, and the delights of a superb arpeggiator.

Many of these features were later to be found on the DX7II, a bold attempt to rectify the occasional DX7 foible, especially concerning the MIDI specs (the DX7 came out in the same year as MIDI and is understandably a bit limited - the ability to send out only on MIDI channel 1 and lack of a local off setting being the two biggest problems). It was unreasonable to expect the Mark II to live up to its illustrious forebear; most feel that some quite major improvements to the sound quality and improved programming possibilities through patch layering and microtonal tuning were offset by a sluggish keyboard response (too much processing going on)."

![]()

|

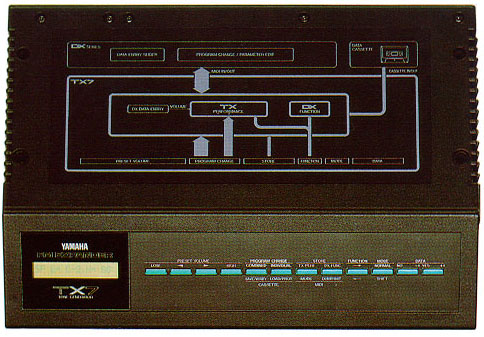

The TX7 was the table-top "expander" version of the phenomenally successful DX7 synthesiser. As well as acting as a synthesiser in its own right, it provided extra storage for "performance" patches for a DX7, which only has one global performance setup. The intention was that the DX7 and TX7 be linked so that the TX would download performance information to the DX as patches were selected.

The TX7 had a front panel editing interface for the performance data, but not for the onboard patches. Other than that, the voice architecture was identical to the DX7's. The "clock radio" casing of the unit, although not as bizarre as that of the TQ5, was inconvenient, and there are better FM sound modules around, from the cheap and cheerful 4-operator TX81Z to the beefy TX802 and TG-77.

The TX7 incorporates the same FM tone generation system found Yamaha DX series Digital Programmable Algorithm synthesizers and the Yamaha TX216 and TX816 tone generator system. This is a six operator, 32 algorithm FM system which is programmable via the DX series synthesizers having the corresponding tone generator - DX7 and DX1 for example. Voices programmed on any 6 operator series of generator or synth can be loaded into the TX7 via MIDI interface and voices in the TX7 can be loaded into any generator or synth.

The TX7 has 32 voice memories, each of which contains the data for one complete 6-operator FM voice. Any voice can have its own set of function parameters and can be fully programmed, including pitch and mod wheels, aftertouch, portamento, and foot controllers to name a few.

![]()

![]()

Thank you for visiting my 'Yamaha DX7/TX7' page. I am always on the look-out for Yamaha DX7/TX7 patches. The synthesizer is getting a bit long in the tooth now, and gradually patches are going to become more difficult to source. By archiving as many as I can get my hands on, I am doing my part in ensuring that current and future owners of the Yamaha DX7 or TX7 can have easy access to as many patches as they desire. If you have any I don't, zip the *.syx (or other) file along with a readme.txt file containing your name, E-mail address, and any other relevant information. E-mail me with the zip file attached. Thank you.

|

|

|

![]()